Remembrance

Remembrance does not glorify war and the red poppy is a sign of both Remembrance and hope for a peaceful future. Wearing a poppy is is never compulsory but is greatly appreciated by those who it is intended to support. When and how you choose to wear a poppy is a reflection of your individual experiences and personal memories.

This year is the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. It was the most devastating and lethal war in history. The Royal British Legion will pay tribute to the Second World War generation, from British, Commonwealth and Allied Forces, in marking VE Day (8th May) and VJ Day (15th August).

The Royal British Legion will mark the service and sacrifice of the armed forces in these and other wars.

- We remember the sacrifice of the Armed Forces community from United Kingdom and the Commonwealth.

- We pay tribute to the special contribution of families and of the emergency services.

- We acknowledge innocent civilians who have lost their lives in conflict and acts of terrorism.

We unite across faiths, cultures and backgrounds to remember the service and sacrifice of the Armed Forces community from United Kingdom and the Commonwealth. It could mean wearing a poppy in November, before Remembrance Sunday. It could mean joining with others in your community on a commemorative anniversary. Or it could mean taking a moment on your own to pause and reflect. We will remember them.

Today’s Anniversaries

74th

anniversary

Image by M. J. Davey, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle of the Imjin River

24th April 1951

The Battle of the Imjin River took place 22nd–25th April 1951 during the Korean War.

The section of the UN line where the battle took place was defended primarily by British forces of the 29th Infantry Brigade, consisting of three British and one Belgian infantry battalions supported by tanks and artillery. Despite facing a greatly numerically superior enemy, the brigade held its general positions for three days.

Though minor in scale, the battle’s ferocity caught the imagination of the world, especially the fate of the 1st Battalion, The Gloucestershire Regiment, which was outnumbered and eventually surrounded by Chinese forces on Hill 235. In this action the Glorious Glosters were awarded two Victoria Crosses.

The Glosters’ stand had plugged a large gap in the 29th Brigade’s front on Line Kansas which would otherwise have left the flanks of the ROK 1st and US 3rd Divisions vulnerable. General James Van Fleet, commander of the US Eighth Army, described the stand as “the most outstanding example of unit bravery in modern war”. The 29th Brigade commander, Brigadier Thomas Brodie, christened the regiment The Glorious Glosters and Hill 235 became known as Gloster Hill.

We will remember them.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Imjin_River

///measures.insiders.given

The Exhortation

Photo: Sgt Dan Harmer, RLC/MOD, cropped, OGL v1.0OGL v1.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Exhortation is recited at the start of every RBL meeting. It consists of the fourth stanza of the poem “For the Fallen” written by Laurence Binyon, CH (10 August 1869 – 10 March 1943) and is also known as the “Ode of Remembrance”.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

There is a French version, often used in Canadian Remembrance services, known as the Acte du Souvenir.

Ils ne vieilliront pas comme nous, qui leur avons survécu.

Ils ne connaîtront jamais l’outrage ni le poids des années.

Quand viendra l’heure du crépuscule et celle de l’aurore,

nous nous souviendrons d’eux.

The Kohima Epitaph

Image by Shyamal, cropped and straightened, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Kohima Epitaph is often recited at the end of each RBL meeting. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), the original version of the epitaph actually inscribed on the temporary Memorial Tablet which General Slim unveiled at Kohima in November is the one now inscribed on the permanent War Memorial. The author was Major John Etty-Leal, the GSO Ⅱ of the 2nd Division. He was a classical scholar, and had imperfectly remembered the verse attributed to John Maxwell Edmonds (1875–1958) in World War Ⅰ, in about 1916. It is now carved on the memorial of the 2nd British Division in Kohima cemetery in Nagaland, India.

The Battle of Kohima was the turning point of the Japanese U-Go offensive into India in 1944 during the Second World War. The battle took place in three stages from 4th April to 22nd June 1944 around the town of Kohima, now the capital city of Nagaland in Northeast India. The War Cemetery in Kohima of 1,420 Allied war dead is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and is located at ///hilltop.copes.bitter. The epitaph has become world-famous as the Kohima Epitaph:

When you go home,

Tell them of us and say,

For your tomorrow,

We gave our today.

For the Fallen

This image is in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“For the Fallen” is a poem written by Laurence Binyon. It was first published in The Times in September 1914. It was also published in Binyon’s book “The Winnowing Fan : Poems On The Great War” by Elkin Mathews, London, 1914. Binyon composed the original poem while sitting on the cliffs between Pentire Point and The Rumps in north Cornwall. The fourth stanza is known as the ‘Ode to Remembrance’ or the ‘Exhortation’.

With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children,

England mourns for her dead across the sea.

Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit,

Fallen in the cause of the free.

Solemn the drums thrill; Death august and royal

Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres,

There is music in the midst of desolation

And a glory that shines upon our tears.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted:

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again;

They sit no more at familiar tables of home;

They have no lot in our labour of the day-time;

They sleep beyond England's foam.

But where our desires are and our hopes profound,

Felt as a well-spring that is hidden from sight,

To the innermost heart of their own land they are known

As the stars are known to the Night;

As the stars that shall be bright when we are dust,

Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain;

As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness,

To the end, to the end, they remain.

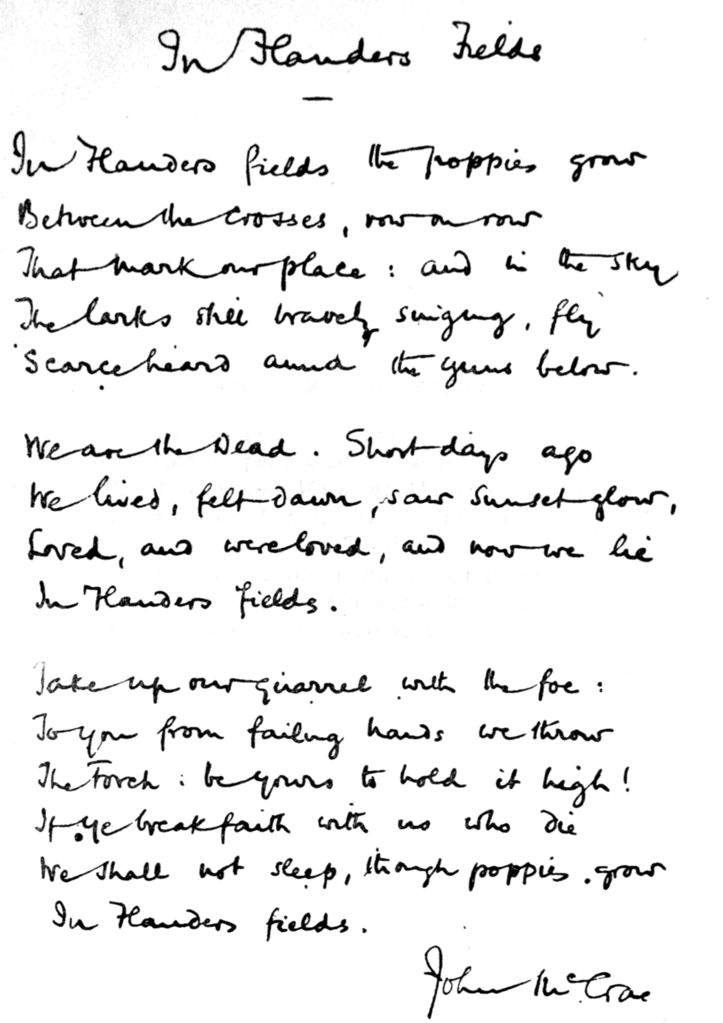

In Flanders Fields

Unlike the printed copy in the same book, McCrae’s handwritten version ends the first line with “grow”.

This image is in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“In Flanders Fields” is a war poem in the form of a rondeau, written during the First World War by Canadian physician Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae. He was inspired to write it on 3rd May 1915, after presiding over the funeral of friend and fellow soldier Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, who died in the Second Battle of Ypres.

Inspired by the poem, American professor Moina Michael resolved at the war’s conclusion in 1918 to wear a red poppy year-round to honour the soldiers who had died in the war. She distributed silk poppies to her peers and campaigned to have them adopted as an official symbol of remembrance by the American Legion. Anna Guérin attended the 1920 convention where the Legion supported Michael’s proposal and was inspired to sell poppies in her native France to raise money for the war’s orphans. In 1921, Guérin sent poppy sellers to London ahead of Armistice Day, attracting the attention of Field Marshal Douglas Haig. A co-founder of The Royal British Legion, Haig supported and encouraged the sale.

In Flanders Fields, the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

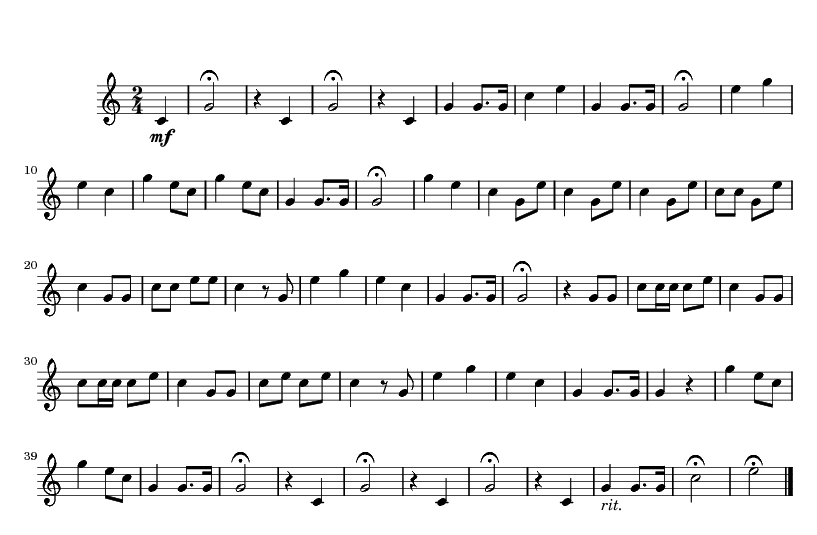

The Last Post

Image by EnEdC, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The “Last Post” performed by Sgt. Codie L. Williams, USMC, on a Soprano bugle in G

This recording is in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Service of Remembrance in many Commonwealth countries generally includes the sounding of the “Last Post”.

First published in the 1790s, the “Last Post” call originally signalled merely that the final sentry post had been inspected, and the camp was secure for the night. In addition to its normal garrison use, the “Last Post” call had another function at the close of a day of battle. It signalled to those who were still out and wounded or separated that the fighting was done, and to follow the sound of the call to find safety and rest.

The “Last Post” is either an A or a B♭ bugle call, primarily within British infantry and Australian infantry regiments, or a D or an E♭ cavalry trumpet call in British cavalry and Royal Regiment of Artillery (Royal Horse Artillery and Royal Artillery).

The “Last Post” as sounded at the end of inspection typically lasted for about 45 seconds; when sounded ceremonially with notes held for longer, pauses extended, and the expression mournful, typical duration could be 75 seconds or more.

For ceremonial use, the “Last Post” is often followed by “The Rouse”, or less frequently the longer “Reveille”.

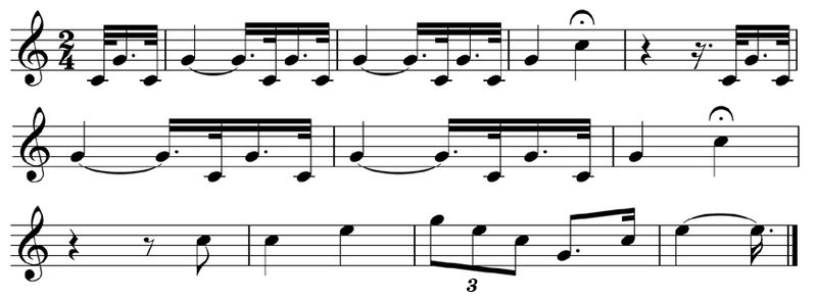

The Rouse

This file is in the public domain because its copyright has expired in countries with a copyright term of no more than the life of the author plus 100 years.

“The Rouse”

This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

“The Rouse” is a bugle call commonly played following “Last Post” at military services. Despite often being referred to by the name “Reveille”, “The Rouse” is actually a separate piece of music from the traditional “Reveille”.

“The Rouse” was traditionally played following “Reveille”, which was the bugle call played in the morning to wake up the troops. “The Rouse” would be played to get soldiers to “Stand to”.

The “Last Post” is played at the beginning of the two-minute silence and “The Rouse” is played at the end of the silence. It essentially turns the two-minute silence into a ritualized night vigil.

Being bugle music, both “The Rouse” and “Reveille” are composed entirely from the written notes of the brass instrument’s harmonic series C major (i.e. C, G, C, E, G etc), these being the only notes available on the instrument.